LEGAL, ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL BARRIERS OF INTRODUCTION OF LOW EMISSION ZONE IN POLAND

Author: Mgr Aleksander Kuś[1]

Research paper conducted under the supervision of Prof. Fabrizio Giulimondi, prepared at academic lecture „Economic analysis of law” at Colege of Legal Sciences Nicolaus Copernicus Superior School.

Warsaw, 2024

Summary: Regulations restricting ownership and the utilisation of private vehicles are on the rise to improve the efficiency and quality of transport systems worldwide. Rising levels of congestion, local air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions drive decision makers to adopt strategic policies to restrict traffic. LEZs have now been introduced in many European countries (mainly in capital cities), but after a period of operation, some countries have abandoned the idea (e.g. state of Germany Baden-Württember, Hamburg, Hanover).[1] In Poland, urban traffic restrictions will take effect on the 1st of July 2024. The doctrine's view, according to the concept of economic analysis of law, is that the purpose of implementing the law is to maximize social wealth and thereby minimize social costs.[2] The imposition by policymakers of solutions that harm citizens' fundamental rights and freedoms in order to limit communications emissions may violate the constitutional principle of proportionality.[2]

Keywords: low emission zone, proportionality principle, economic analysis of law, environmental protection, freedom of movement.

1. Introduction

Low Emission Zone (LEZ)[3] is geographically defined area or roads banning or restricting access for polluting vehicles, typically within urban region. The primary aim of LEZ is to reduce air pollution, particularly pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PM), by encouraging the use of cleaner vehicles or alternative modes of transportation, especially in problem areas.

Vehicles need to meet certain emissions standards to drive within the LEZ. CAZs could potentially apply to all vehicles but generally apply to heavy diesel vehicles due to their relatively large contribution to air pollution. Some LEZs allow non-compliant vehicles to enter the zone by charging a fee. Zones that completely ban all vehicles running on an internal combustion engine and only allow electric-powered vehicles to enter are called Zero Emission Zones (ZEZ).[3]

LEZ is a tool used alongside other measures to reduce harmful emissions, it is not possible to attribute to them a specific contribution to the reduction of such emissions. The full picture of the costs will only become clear a few years after the introduction of the zone or after it has adopted its final shape.

2. The shape of the automotive market in Poland.

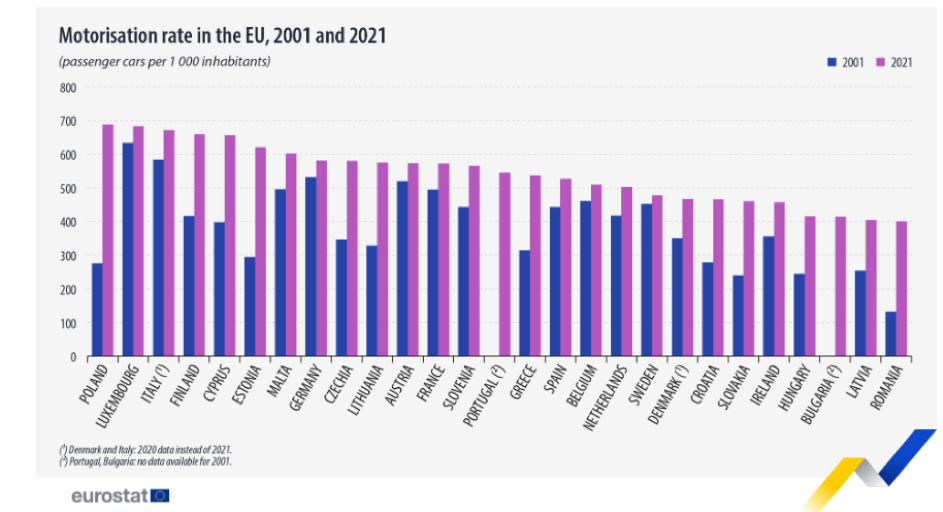

Graph 1. Motorisation rate in EU (2000 and 2021).

(Source: Eurostat, Data Browser[4]).

EUROSTAT research shows that Poles are EU leaders in the number of cars owned (Graph 1). In 2021, Poland had the highest number of registered passenger cars in the entire European Union (687) per 1,000 inhabitants. Poland has the oldest cars in the European Union.[5] 253.3 million passenger cars were registered in the European Union in 2021. Most in Germany (48.5 million), Italy (39.8 million) and France (38.7 million). Poland ranked fourth in this respect (25.8 million) and was slightly ahead of Spain (24.9 million). In 2021, Poland had the highest percentage of registered passenger cars over 20 years old in the European Union (41.3 %), Estonia (33.2 %) and Finland (29.1 %) were also on the podium.[6]

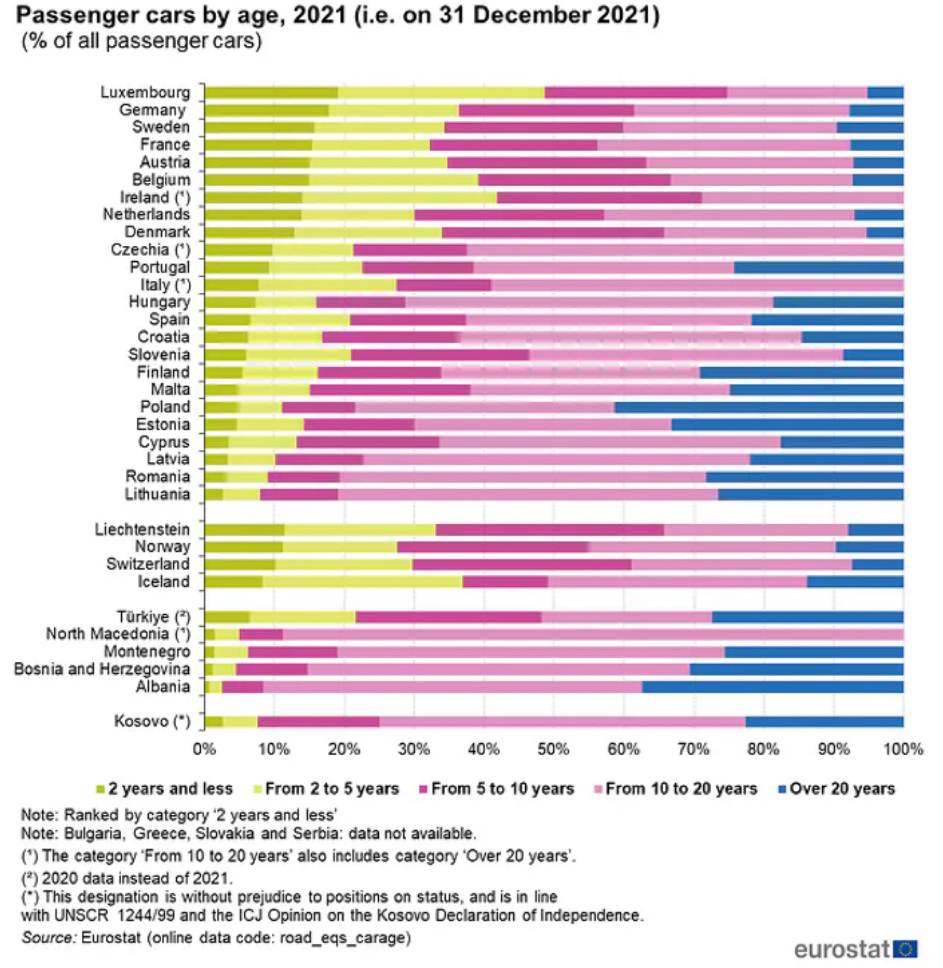

In order to outline the socio-financial situation of the Polish citizens, indicator of motorisation rate should be contrasted with number of Polish passenger cars by age in 2021 (Graph 2). This comparison is a good illustration of social inequality in Poland.

Graph 2. Passenger cars by age in 2021.

(Source: Eurostat, Database [7])

According to eurostat surveys, Poles drive the oldest cars on the Old Continent – 41.3 % of cars in Poland are over 20 years old (37.1 % are 10-20 years old, less than 5 % are two years old or less). Apart from the Poles, the oldest cars are driven by Estonians (33.2% of cars over 20 years old) and Finns (29.1% of cars over 20 years old). In contrast, Luxembourg (5.2 %), Denmark (5.3 %) and the Netherlands (7 %) have the fewest cars over 20 years old, which could be explained by the relatively low income level in Poland (compared to the EU) – people are more likely to drive older cars or import used cars from other countries. In Poland, the average age of cars is one of the highest in Europe, influenced by factors such as financial accessibility (Polish incomes are relatively lower than those of other Europeans), the legacy of economic transformation, a well-developed second-hand car market, the lack of restrictions on the age of registered cars, or culture and lifestyle (pragmatism and frugality).

The two statistical indicators cited above clearly illustrate the economic situation in the car market in Poland. In 2021. Poland had the most passenger cars in the entire European Union per 1,000 inhabitants, as well as there were the oldest cars in the Old Conctinent. Concluding, the level of wealth of Poles will not allow the smooth purchase of new low-emission cars. Forced implementation of the new LEZ regulations could introduce major changes in the market – which will affect the impoverishment of citizens.

3. Plan for introduction of LEZs in Poland.

The transformation currently under way in the battle for clean air is taking place on many fronts. In Poland a growing number of lawsuits are being brought before common courts related to exceeding permissible concentrations of harmful substances in the air. environmental organisations are even attempting to file administrative complaints about the sluggishness of public administration bodies and their ineffective anti-smog policies.[8] The problem therefore becomes urgent. This is evidenced by the fact that in early February 2021 the European Commission called on Poland to comply with the requirements of Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe [9]. Clean Transport Zones (CTZ), an institution introduced into the Polish legal system by the Act of 11 January 2018 on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels (AEAF)[10], implementing Directive 2014/94/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on 22nd of October 2014 on the development of alternative fuels infrastructure[11].

In Poland, plans to create such zones have so far aroused much public resistance. The Autobase internet service carried out a survey asking for opinions on Clean Transportation Zones. 40 % of those surveyed said they were against the creation of such zones, while only 25 % supported it. LEZ in Poland are met with great dissatisfaction among citizens.[12]

Next year, the first two Polish cities - Krakow and Warsaw[4] - are to establish them. However, despite the universality of this solution in Western European countries, it is still highly controversial in Poland. In the first phase, which is expected to take effect from July 2024, the ban will apply to petrol cars that do not meet the Euro 1 standard or were manufactured before 1992 and, for diesels, those that do not meet the Euro 2 standard or were manufactured before 1996. From 2026, the restrictions will be increased to Euro 3 for petrol cars and Euro 5 for diesel cars. The next phase will be implemented in 2028. The restrictions will cover around 16 % of the cars used in Warsaw. The next one is planned from 2030. Then as many as 23 % of cars will not enter the LEZ, and two years later, with another restriction, 27 % of cars. The no-entry rules will apply to everyone – residents, visitors and tourists alike.[13]

Should be emphasized that public transportation in Polish cities is still much less convenient and developed than in Western European cities (for example, there are only two subway lines in the Polish capital, 9 in Berlin and 12 in London), and getting around there takes much more time than with one's own car.

4. Arguments against implementing Low Emission Zone.

The first of the main arguments against the introduction of LEZs is economic. Businesses operating within the LEZ may face significant costs associated with upgrading their fleets to meet emissions standards. This includes the cost of purchasing new vehicles or retrofitting existing vehicles with cleaner technology, which could strain the finances of small or medium-sized businesses. Companies that are reliant on transport as part of their supply chains could be at risk of disruption if their suppliers or logistics partners are unable to meet the emissions standards. This could lead to delays in the receipt of goods or increased transportation costs, which could affect the overall efficiency and profitability of companies. If companies face financial difficulties or reduced competitiveness as a result of the LEZ, they may be forced to downsize or close operations, resulting in job losses in affected industries. This could have broader economic consequences, including reduced consumer spending and tax revenues.[14]

There is a risk that businesses will relocate outside the LEZ to avoid compliance costs, resulting in a shift of economic activity away from the city center. This could lead to a decline in property values and commercial activity within the zone, negatively impacting local businesses and property owners. Certain industries, such as construction, logistics, or manufacturing, may be disproportionately affected by the regulations due to their reliance on heavy-duty vehicles or equipment that produce higher emissions. These businesses may struggle to adapt to the requirements of the LEZ, resulting in economic hardship for workers and stakeholders in these industries. Compliance with the regulations may impose additional administrative burdens on businesses, such as recordkeeping requirements or the need to apply for permits or exemptions.

The second major argument against the introduction of LEZs is one of social equity. There may be concerns that the costs of compliance will fall disproportionately on low-income individuals or those who cannot afford to upgrade to cleaner vehicles. This could exacerbate existing inequalities by penalizing those who are already economically disadvantaged. Restrictions on high-emission vehicles could impede the mobility of certain groups, such as residents who rely on older vehicles or businesses that need access to downtown areas. This could lead to inconvenience and reduced accessibility for those affected.

Another argument is that restrictions on high-emission vehicles within the zone may simply shift pollution to areas outside the zone, rather than actually reducing overall emissions. This could have unintended consequences, such as an increase in pollution levels in nearby neighborhoods.

The fourth argument against the introduction of the LEZ is legal barriers. Government interference with civil liberties Government overreach. Some individuals or groups may view the implementation of an LEZ as an unnecessary government intrusion or infringement on personal freedoms, especially if they feel that the benefits do not outweigh the costs.

Finally, public opinion is increasingly arguing that clean transport zones discriminate against less well-off Poles who are forced to get rid of their older cars. This could lead to a widening of the social gap between rich and poor.

5. Advantages of introducing the LEZs.

The Constitution of the Republic of Poland guarantees citizens the protection of the environment and public health, which should be ensured by the LEZ. Article 74th of the Polish Constitution states that the State shall ensure health and safety at work and protect the health of workers, which can be interpreted as supporting measures to reduce emissions of pollutants that may harm the health of workers and residents. Similarly, Article 5th of the Polish Constitution states the need to respect human rights, including the right to a healthy environment, which can provide a basis for measures to improve air quality.

The first argument supporting the thesis of the necessity of a clean air zone is the Improving Public Health. CAZs aim to reduce air pollution levels, particularly harmful pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM). By reducing exposure to these pollutants, CAZs can improve public health outcomes, including reducing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. The WHO estimates there were 4.2 million[15] premature deaths related to outdoor air pollution in 2019: “some 37% of outdoor air pollution-related premature deaths were due to ischaemic heart disease and stroke, 18 % and 23 % of deaths were due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] and acute lower respiratory infections respectively, and 11% of deaths were due to cancer within the respiratory tract”.[16]

Further argument about advantages of introducing LEZ is environmental protection. CAZs contribute to environmental protection by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants, thereby helping to mitigate climate change and protect ecosystems.

Thirdly, meeting legal obligations. Many cities are legally required to improve air quality to comply with national and international regulations, such as the EU air quality directives. Implementing LEZs can help cities meet these legal obligations and avoid potential fines for non-compliance. The stringent regulations imposed by the European Union – if not transposed into national law – carry heavy penalties.

LEZs can benefit disadvantaged communities that are disproportionately affected by air pollution (e.g., communities near busy roads or industrial areas). By improving air quality, LEZs help reduce health inequities and promote environmental (social) justice. Cleaner air contributes to a higher quality of life for residents by reducing health risks associated with air pollution, increasing opportunities for outdoor recreation, and creating a more pleasant urban environment.

6. Legal barriers to implementing LEZ in light of the Polish Constitution.

Article 5 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland places the protection of the environment relatively high among other objects of protection. This circumstance proves the importance given by the legislator to the protection of the environment. At the same time, the order of the values listed in the said provision testifies to the priorities set for their protection.[17] Environmental protection must be implemented in accordance with the principle of sustainable development.

The Polish legislator assumed that fulfilling the obligation to protect the environment (including health), may require the restriction other constitutional freedoms and rights. This is a consequence of the importance attached to the protection of the environment. Article 31 section 3 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland stipulates that restrictions on the exercise of constitutional freedoms and rights may be established only by statute and only when they are necessary, among others to protect the environment and the health of other persons. It is necessary to emphasize that the indicated restrictions must not violate the essence of these freedoms and rights. It should therefore be recognized that they must be introduced in accordance with the principle of proportionality.[18]

The establishment of the LEZ involves a ban on certain types of motor vehicles entering its area. This can result in the restriction of a number of rights of the owners of such vehicles., i.e.: freedom of movement within the territory of the Republic of Poland (which is formulated in Article 52(1) of Constitution), the right to property (included in Article 64(1) of the Constitution), freedom to choose and pursue a profession and to choose the place of work (referred to in Article 65(1) of the Constitution), and the right to safe and hygienic working conditions (referred to in Article 66(1) of the Constitution). The consequence may also be a restriction of the right to health protection, including the provision of special health care for children, pregnant women, disabled people and the elderly, the right to assistance for disabled people and equal access to education.[19]

Both the resolutions on the establishment of LEZ and some ways of interpreting Article 39 of the Act on Electromobility and Alternative Fuels[5] may violate the provisions of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland. The dispute should concern the proportionality of the exercise of individual rights and freedoms and, at the same time, their limitation in the conditions in which they must be exercised in parallel.[20]

7. Financial capabilities of the Polish population.

LEZs are a specific instrument of urban policy. The effectiveness of the changes introduced to implement LEZs is relatively dependent on the financial situation in Poland. An important issue is whether Poles are able to bear the financial costs of introducing LEZs.[21]

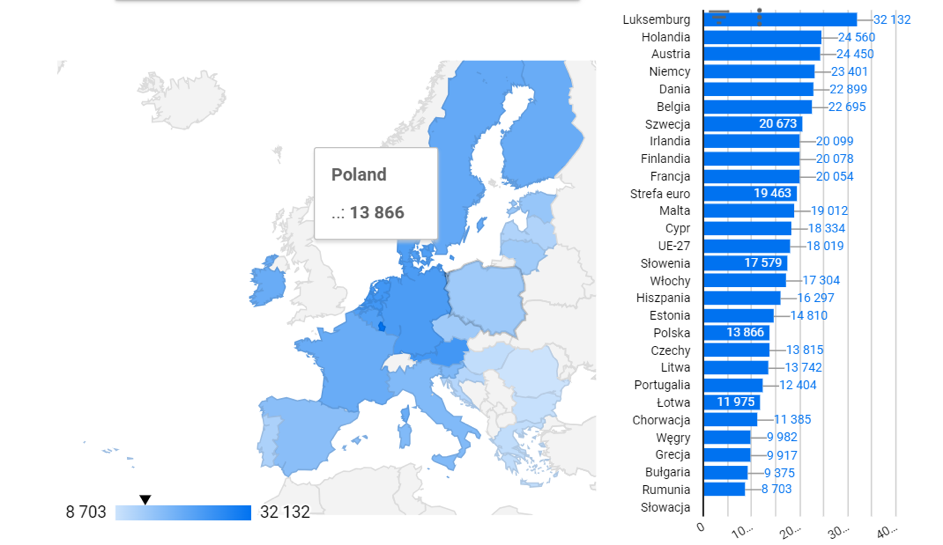

Graph 3. Median net equivalent income (purchasing power standards PPS) in EU countries in 2021.

(Source: Eurostat, DataBase[22])

Important measure of income distribution is the median equivalent disposable income (median disposable income) expressed per capita in the purchasing power standard (PPS). In Poland, the median disposable income in 2021 was PPS 13,866, which puts Poland 10th from the bottom, between Estonia and the Czech Republic. If we express income in euros, Poland's position changes for the worse – fall to 5th position from the bottom. According to Eurostat, in 2021 the median disposable income in Poland was EUR 8,295.[23]

Graph 1 in comparison with Graph 2 informs that, on the one hand, Poland has the most cars per 1,000 inhabitants in the EU, however, on the other hand, the country's wealth index (PPS) is at a low level, Poland ranks 10th in Europe. To sum up, there are a lot of old cars in Poland, whose owners are relatively (at the EU level) not wealthy. The introduction of the LEZ will limit the use of cars by Poles and force them to buy new models that meet ecological standards. As a result, Poles will incur high financial costs and their financial situation will deteriorate. In 2021, the purchasing power of money in Poland will be 45 % lower than the European average (PPS 19 463). Opportunities for Poles to buy new cars that meet ecological standards are relatively small.

8. The future of CTZs in Poland – conclusions.

Current international research on the introduction of clean air zones indicates that the introduction of LEZs in many European cities resulted in negative social and economic effects. This is well illustrated by the conclusions from the scientific research The economics of low emission zones, carried out by M. Börjesson, A. Bastian and J. Eliasson, published in "Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice"[24]:

„We find that the social benefits of the air quality improvements are less than a tenth of the social cost. Enforcement costs also add to the social costs of an LEZ (Milan, for instance, uses camera enforcement), although we do not attempt to quantify them. Even if our empirical results must be interpreted with caution, it seems clear that the costs considerably outweigh the benefits in this case study

(…)

Air quality effects of LEZs are difficult to determine ex-post. Meteorological variations call for long measurement periods (Pasquier and Andre, 2017) and LEZ benefits quickly diminish due to natural vehicle fleet renewal (Carslaw and Beevers, 2002). Wolff (2014) concludes that Germany’s largest LEZs reduced particle pollution, while smaller zones had small or no benefits. Johansson et al. (2014) corroborate this relationship between zone size and effectiveness. Malina and Scheffler, 2015, Ellison et al., 2013, Morfeld et al., 2014, and Holman et al. (2015) conclude that some LEZs had small air quality benefits while others had none. Effectiveness also depends on which pollutant is measured. Particle pollution mostly depends on total traffic volume (Amato, 2018), and OECD (2020) report that because electric cars are heavier than other cars, is unlikely that they will emit less particles. Nitrogen oxide pollution, however, depends on the specific traffic composition and its emission „characteristics.”

According to the latest report from the European Environment Agency, exposure to PM2.5, NO2 (nitrogen dioxide) and O3 (ozone) caused 5330 premature deaths in Belgium in 2020[25]. Following the introduction of the LEZ in 2018, NO2 concentrations along the main roads in Brussels were reduced to 30%. Between June of 2018 and September of 2022, the share of diesel vehicles on the roads was almost halved as a result of the legal restrictions[26]. This has changed the profile of the car market in the Belgian capital. Citizens were restricted by the state in depriving them of the freedom to drive their cars, which could have caused social tensions.

An effective solution to the need to introduce LEZ zones in Poland is to gradually (at large intervals) introduce such zones, as well as lower the exhaust gas production limit – so that citizens can internally convince themselves of the validity of this project. The idea of a LEZ is justified to be introduced, but in order to take this step, society must be prepared for it.

From an economic point of view, the introduction of an LEZ in Poland will lead to changes in the daily life of the inhabitants of large and medium-sized Polish cities. Entrepreneurs will have to adapt to these changes, which will result in additional financial operating costs and discourage investment in the affected areas. This may hinder the economic growth and development within the zone and decrease competitiveness on the market.

The introduction of LEZ may be discussed and interpreted in terms of various constitutional principles, including freedom of movement or equality before the law. The final assessment of the compatibility of the introduction of the LEZ with the Polish Constitution would be made by the Constitutional Tribunals on the basis of individual cases and legal arguments presented by the parties to the dispute.

In conclusion, the idea of introducing LEZs in Poland is objectively justified and efforts should be made by EU member states to implement it. However, it seems wrong for the EU to impose the rigors of the LEZ at a time when the country is not economically prepared for such a considerable change. The proposed solution will not be consistent with the Pareto optimality principle, according to which it is impossible to make any individual better off without making at least one individual worse off. The allocation of resources in the case of the Polish LEZ could prove to be an inconvenience. Polish society is not prepared for the introduction of LEZs due to the high price of the project. As the presented research shows, a large part of Poles do not agree with the introduction of LEZs. The social costs of LEZ implementation exceed the financial costs of this project.

Bibliography:

[1] Green-Zones.eu, Germany: (Also) these cities will abolish environmental zones, 03.05.2023, in „https://www.green-zones.eu/en/blog-news/baden-wuerttemberg-many-environmental-zones-abolished-1”.

[2] W. Załuski, Cel prawa według Law and Economics, in J. Czapska, M. Dudek, M. Stępień, „Wielowymiarowość prawa”, Toruń 2014, s. 299.

[3] V. Weinmann, Low Emission Zone (LEZ) Vehicle Travel Restriction to Improve Air Quality in Inner Cities, report "Transport Demand Management in Beijing Emission Reduction in Urban Transport”, in „https://tuewas-asia.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/20140702-Low-Emission-Zones-Factsheet_EN.pdf”, pages: 1-9.

[4] Eurostat, Data Browser, „Stock of vehicles by category and NUTS 2 regions”, 13.10.2023, in „https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/TRAN_R_VEHST__custom_6385961/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=8dee8b9a-0c4f-4f1d-b24c-999f39c62a35”.

[5] Rzeczpospolita, „Polacy mają najwięcej aut w UE. Niestety 41 proc. z nich ma ponad 20 lat”, 23.08.2023, in „https://moto.rp.pl/czym-jezdzic/art38986081-polacy-maja-nawiecej-aut-w-ue-niestety-41-proc-z-nich-ma-ponad-20-lat”.

[6] Eurostat, „Number of cars per inhabitant increased 2021”, 30.05.2023, in „https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230530-1”.

[7] Eurostat, Statistics Explained, „Passenger cars in the EU”, 11.2024, in „https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Passenger_cars_in_the_EU”.

[8] S. Pawłowski, A model of introducing Clean Transport Zones in Poland – between optionality and obligatoriness, in "Dyskurs Prawniczy i Administracyjny", Oficyna Wydawnicza Uniwersytetu Zielonogórskiego, 2/2022, Zielona Góra 2022, p, 51-72.

[9] Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on ambient air quality and cleaner air for Europe, Official Journal of the European Union, L 152, 11.06.2008, in „https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?toc=OJ:L:2012:112:FULL&uri=OJ:L:2008:152:TOC”.

[10] ISAP, Ustawa z dnia 11 stycznia 2018 r. o elektromobilności i paliwach alternatywnych (Dz.U. 2018 poz. 317), in „https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20180000317”.

[11] Directive 2014/94/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 on the deployment of alternative fuels infrastructure, Official Journal of the European Union, L 307, 28.10.2014, in „https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ%3AL%3A2014%3A307%3ATOC”.

[12] J. Krzemiński, Większość Polaków nie chce Stref Czystego Transportu, Portal Samorządowy, 27.02.2023, in „https://www.portalsamorzadowy.pl/ochrona-srodowiska/wiekszosc-polakow-nie-chce-stref-czystego-transportu,443694.html”.

[13] Rzeczpospolita, Już w 2024 roku tymi samochodami nie wjedziesz do Warszawy, 20.09.2023 r., in „https://moto.rp.pl/ekologia/art39136691-juz-w-2024-roku-tymi-samochodami-nie-wjedziesz-do-warszawy”.

[14] S. Quadir, Expanding London’s Ulez has sparked fractious debate – psychologists explain how it can be de-escalated, in "City, University of London", in „https://www.city.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/2023/10/expanding-londons-ulez-sparked-fractious-debate-psychologists-explain-how-can-be-de-escalated”.

[15] World Health Organization (WHO), Ambient (outdoor) air pollution, 19.12.2022, in „https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health”.

[16] The truth about London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone, in The London School of economics and political science. Grantham Research Institute On Climate Change And The Environment, 24.08.2023, in https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/the-truth-about-londons-ultra-low-emission-zone/.

[17] Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 2 kwietnia 1997 r., Dz.U. 1997 nr 78 poz. 483, art. 5.

[18] T. Woźniak, Strefy Czystego Transportu. Idea i praktyka funkcjonowania, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Instytutu na rzecz Kultury Prawnej Ordo Iuris, Warszawa 2024, p. 91-93.

[19] Ibidem, p. 92-95.

[20] Ustawa z dnia 11 stycznia 2018 r. o elektromobilności i paliwach alternatywnych (Dz.U. 2018 poz. 3170).

[21] T. Woźniak, Strefy… op. cit., p. 84-85.

[22] Eurostat, Data Browser, „Mean and median income by age and sex - EU-SILC and ECHP surveys”, 17.04.2024, in „https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ILC_DI03__custom_4387934/bookmark/table?lang=en&bookmarkId=609d6721-3883-4186-bdea-9d6dfad5dc62”.

[23] Forsal.pl, Bieda i bogactwo w UE. Jak na tle Europy wypadają dochody Polaków?, 16.03.2023, in https://forsal.pl/finanse/finanse-osobiste/artykuly/8634696,dochod-do-dyspozycji-polska-na-tle-ue-eurostat-nierownosci.html.

[24] M. Börjesson, A. Bastian, J. Eliasson, The economics of low emission zones, in E. Cherchi "Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice", Volume 153, November 2021, pages 99-114.

[25] European Environment Agency, Report Health impacts of air pollution in Europe 2022, 24.11.2022, in „https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2022/health-impacts-of-air-pollution”.

[26] Brussels Environment, Rapport technique: La Qualité De L’air En Région De Bruxelles-Capitale Rapport Annuel 2022, 11.07.2023, in „https://document.environnement.brussels/opac_css/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10881”.

-----------------

[1] Mgr Aleksander Kuś, PhD Student of Colege of Legal Sciences Nicolaus Copernicus Superior School.

[2] The Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2nd April, 1997 as published in Dziennik Ustaw No. 78, item 483, Article 31 p. 3 states that "Any limitation upon the exercise of constitutional freedoms and rights may be imposed only by statute, and only when necessary in a democratic state for the protection of its security or public order, or to protect the natural environment, health or public morals, or the freedoms and rights of other persons. Such limitations shall not violate the essence of freedoms and rights".

[3] Also: Clean Air Zones (CAZ)/Clean Transport Zones (CTZ).

[4] LEZ was established in Warsaw by a resolution dated 7 of December 2023, with the stipulation that the resulting restrictions would take effect from 1st of July 2024. The SCT in Krakow, established by a resolution dated 23 of November 2022, was to be in effect from the same date. However, in a judgment dated 11st of January 2024 (the case ref. no. III SA/Kr 484/23), the Regional Administrative Court in Krakow declared the resolution invalid, the municipal authorities announced that they would not appeal the decision in cassation. Krakow City Council announced the creation of a new draft resolution establishing the LEZ. Preliminary consultations have also taken place so far in Wroclaw. Preliminary declarations of intent to create a Clean Transportation Zone have been expressed by the authorities of a number of other Polish cities, including: Katowice, Gliwice, Toruń, Bydgoszcz, Rzeszów, Gdańsk and Sopot.

[5] Official publication: Dziennik Ustaw, Number: Dz. U. 2023 poz. 875.